Singapore: From Investment to a Thriving Startup Ecosystem

Berlin, Germany

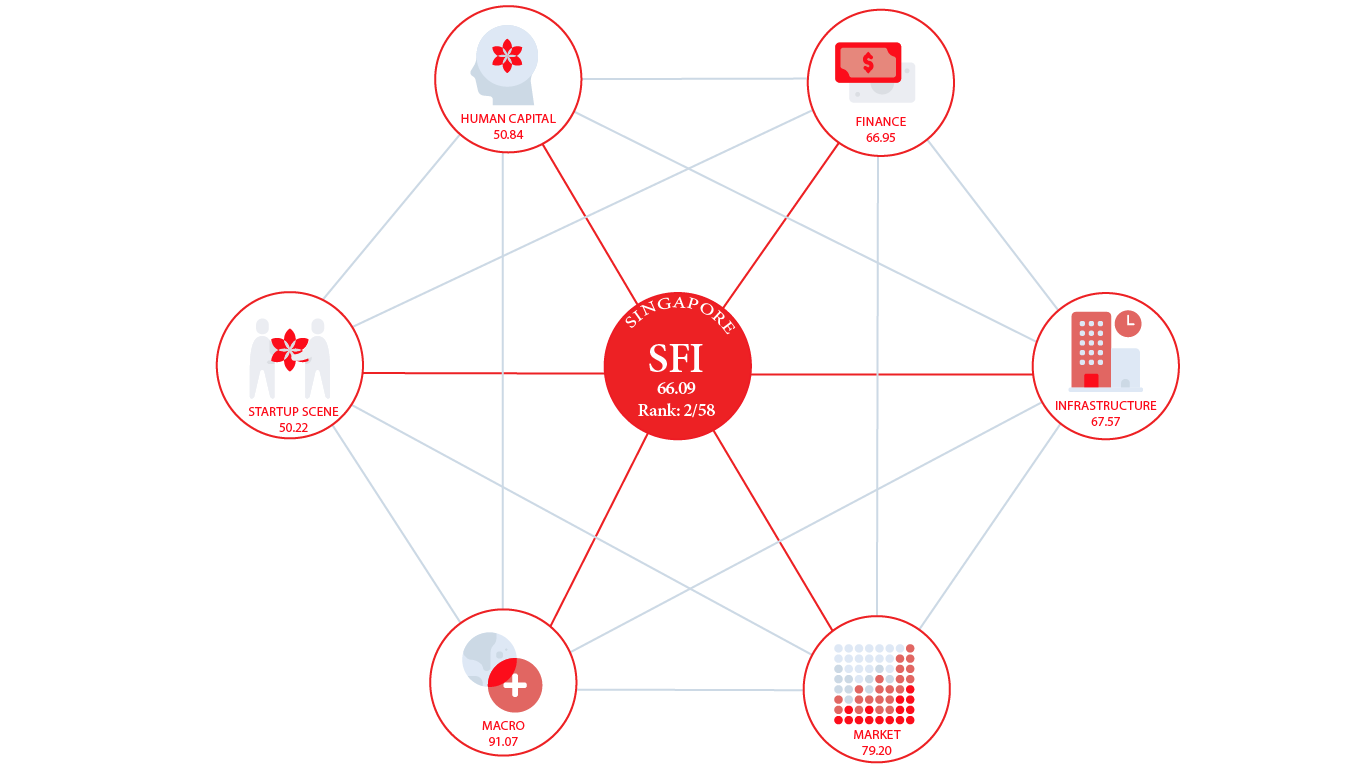

By all indications, Singapore is one of the world’s leading startup ecosystems. The nation state boasts multiple successful startups, indeed, but is also the regional hub for incorporation, venture capital, and international connections. Within our SFI, Singapore is consistently ranked among the highest (66.09), not only in the Asia region but also globally (Berlin with a score of 67.48 is the highest in our index). There are a great many number of distinct factors that make Singapore compelling, and therefore begs the question: how did Singapore create such imminence as a startup ecosystem?

Most of the success Singapore is seeing in its startup scene is a result of a series of economic policy and cultural designs made by the republic as far back as the 1980s. After a worldwide economic recession, the Singaporean government had a realization that they needed a strategy for growth. As a small nation with relatively few natural resources, they instead pivoted to becoming a hub for trade, incorporation, and investment. In this chapter, we will dive deeper into the defining elements of what makes Singapore unique as a startup ecosystem, starting first with an understanding of its startup scene history, analyzing its SFI score, and taking a look at some of its more influential policies. Lastly, our guest articles will take a look at key sectors that influence the Singaporean startup landscape.

startup friendliness performance

Singapore is not only the regional leader in the SFI, but is also among the global leaders, Berlin (67.48) and Hong Kong (63.15). It earns a final SFI score of 66.09 out of 100; its excellent score is mainly driven by its macro-political context as a regional hub for Asia, as well as its strong joint public-private partnerships to encourage and invest in innovation and entrepreneurship. The key area that Singapore struggles to compete in? Access to entrepreneurs.

As early as the 1980s, the national government began to strategize on how to grow their economy without the natural land resources and a bursting population that many of its regional neighbors have. The nation receives a score of 61.18 for R&D expenditure, 99.56 and 99.41 for business registration time and cost, respectively, and 65.45 for its corporate tax. We will dive more into the policies that make Singapore a startup hub in this chapter.

highlights

1. Singapore is one of the primary incorporation hubs of Asia

Alongside Hong Kong, it’s not uncommon for international and regional businesses to incorporate in Singapore due to its favorable corporate tax laws, stability, and ease of international cash transfers.

2. The Singaporean government has focused on entrepreneurship as a path to economic growth

As early as the 1980s, the national government began to strategize on how to grow their economy without the natural land resources and a bursting population that many of its regional neighbors have. The nation receives a score of 61.18 for R&D expenditure, 99.56 and 99.41 for business registration time and cost, respectively, and 65.45 for its corporate tax. We will dive more into the policies that make Singapore a startup hub in this chapter.

3. Access to human capital is Singapore’s growth issue

The problem is not a lack of skilled workers (scored at 98.73), but the lack of entrepreneurs in Singapore who are willing to take the risk of starting their own venture (perception of entrepreneurship as a career path: 42.35). Furthermore, local talent is expensive, especially in comparison to other regional powerhouses.

4. Relatively easy access to startup financing

The first half of 2020 saw over $100m of investment in Singapore. The nation has a very vibrant venture capital and business angel market with networks and firms focusing on different mandates. Singapore ranks first in our index for total number of business angels and loans rejected (best acceptance rate).

Singapore is a regional hub for startups and corporations.

To better understand the intricacies of Singaporean startup landscape, we turned to Michelle Ng. Michelle works for the leading venture capital firm in Southeast Asia and emerging Asia: Quest Ventures. “I believe innovation and startup culture is the way forward to keep Singapore competitive and, at the same time, lift up developing and emerging nations,” Michelle says.

Michelle confirmed what our SFI indicates: Singapore shines in its concerted public-private efforts to boost entrepreneurship, but it struggles to supply the human capital it needs for a more vibrant startup ecosystem. Contributing to its human capital score is its indicator for University Students, a low 3.16. This is mostly owed to its small geographical size and population in comparison to powerhouses such as Jakarta, and the major entrepreneurial cities in India. It is not surprising for large cities that attract a lot foreign talent, as they tend to attract many people who did not study there. This impacts a startups ability to hire low-cost talent many of whom typically look for talent through institutions of higher learning. To account for the high cost of Singaporean talent, the government also helps out: the GRT grant is a government program that encourages startups to hire local talent by subsidizing up to 70% of the intern’s wages.

Compounding the issue could be a cultural fear of failure

According to Michelle, “Much of the young talent is not comfortable with the entrepreneurial mindset. There is no hunger to start and build something of your own. It cannot be taught in formal education,” she laments. “It’s one of the remarkable things about the Jakartan startup ecosystem,” she continued, highlighting that Singapore is unique in its access to entrepreneurial infrastructure but overall lack of interest. Indeed, our index shows that Singapore’s score for Entrepreneurial Culture comes in at 50.11, which in turn pulls down its score for its Startup Scene overall. In our index, Singapore receives a score for just 8.18 for ‘entrepreneurial intentions’ and ranks first (score of 100) for the trait of risk avoidance.

Recent graduates often get lucrative, high-paid jobs in international corporations and their regional offices. Government jobs are additionally well paid. It is simply less attractive to “take the risk” and found a startup.

This is not an uncommon issue for wealthy countries such as Singapore, where young talent can experience comfortable and secure lives at large corporations. To put it in relevant terms, Singapore has the highest average salaries in our index, about a net average of $3811 USD per month. In contrast, there is hardly a need for a minimum wage. The only mandates that exist are those for custodial and security work, for which the minimum is $802 USD per month, giving Singapore a score of 54.31 in our index.

Ideally, the country would like to see more of its own citizens engage in entrepreneurship. “The startup scene is getting more competitive for young talent,” Michelle says. “There are more entrepreneurship programs at institutes of higher learning to encourage students to gain exposure to startups,” such as NUS’ NOC programs and NTU’s Overseas Entrepreneurship Programme, where student are sent to large startup hubs abroad, such as in China or the USA, and are encouraged to “attend local entrepreneurship events like hackathons, innovation competition, and fireside chats with local entrepreneurs.”

However, the country has also faced pressure to balance its need for entrepreneurial talent with the growing pressure of immigration. In 2019, the country saw 2.16 million immigrants. Many come from neighboring countries seeking jobs and eventual citizenship for a better quality of life. Beginning in January 2018, the government raised the minimum earnings needed to qualify for visas into the country. When asked, Michelle said that most businesses were not too affected by the tighter restrictions: “Many companies and startups hire overseas talent and teams based out of Singapore, and they are typically based in Vietnam and Indonesia.” As a policy to curb immigration, it was successful: the nation saw a large drop in foreigners with work visas in 2017 — 32,000 less than the year before.

Indeed, a recent study from International Enterprise Singapore shows that, with encouragement from the government, international Singaporean companies saw 53% of their revenue created abroad, with popular areas for international expansion being China, Myanmar and Vietnam. Of companies who saw a 4.2% increase in overseas revenues, smaller firms lead in earnings.

Still, though finding talent abroad seems popular, our indicators show that Singapore faces the toughest labor regulation constraints in our index: 90% of firms in Singapore indicate that finding and hiring talent was a constraint for their firm.

High tech manufacturing is the future

Singapore is a rich country for rich companies. So their strategy for the future is on its face a bit surprising; a full one-fifth of Singapore’s economy is from manufacturing. Not driven by large-scale consumer manufacturing, Singapore’s pivot is towards high-tech manufacturing. In 1983, Singapore produced 11.5% total manufacturing in comparison to its 2019 levels, and it was mostly driven by textile and apparel production. Today, manufacturing in Singapore is dominated by chemical manufacturing, pharmaceuticals and biological products, refined petroleum products, and other high-tech manufacturing sectors.

It is in this area — DeepTech including high-tech manufacturing — that much of Singapore’s innovation is centered. Here, startups play a large role in driving innovation forward. Singapore has found unique ways to empower startups to merge with industry to drive unique solutions and become a leading exporter for high-tech manufacturing (it is the fourth-largest exporter globally). One such solution is the use of a nearby Indonesian island, Batam, which is being built as a technology park to connect Singapore and Indonesia to “test new ideas” and “co-create new solutions”.

It can be difficult to drive high-tech innovations through startups, as young companies can often struggle to finance new and innovative ideas through the MVP stage in order to scale their businesses up. But our index shows that Singapore fairs well in its funding environment: it ranks among the highest in the index for high equity funding of $5M USD with 5.5% of its startups receiving this level of funding.

The nation-city has a long history of encouraging innovation. In 2011, NUS Enterprise, Media Development Authority, and Singtel Innov8 collaborated to turn Blk 71 into an innovation hub and to attract startups to create an ecosystem. It since was so successful that it’s been expanded into LaunchPad@one-north with more collaborations in the works.

From the beginning of an entrepreneur’s life cycle, Singapore appears well equipped to support startups. What remains to be seen is the depth of its startup’s involvement in its overall economy, including manufacturing, and if it can overcome a shallow talent pool that is willing to engage in entrepreneurship.

Singapore for the future

So where is this ecosystem headed for the future and what trends will define the nature of Singapore’s startup scene?

Michelle sees a few key trends for the future, among them, increased digitalization, and more corporate involvement in the startup scene. She predicts that there will be more venture capital invested with impact built into the funds as well as corporates looking to partner locally with startups to innovate more, and anticipates “a race to see who will emerge as Southeast Asia’s regional champion, [to see] who is going to take the center stage.”

Next, we will take a look at what policies have shaped the Singaporean startup scene and conclude with recommendations for further development.