Let’s Talk about Jakarta: A Close-up of the Blue Ocean City for FinTech

Indonesia as a potential market

Indonesia is the biggest economy in Southeast Asia and has been, for the last few decades, one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. After China, India and the United States of America, Indonesia is the fourth most populous country in the world, though it remains the 16th largest economy.

Despite experiencing a negative migration balance (more emigrants than immigrants), the population is still increasing due to a relatively young population and a high birth rate. With an increasing number of habitants and consistently increased productivity (measured by GDP per capita), Indonesia’s economic growth is closing the gap to bigger economies like the United Kingdom, Brazil, Russia or France, which have been struggling with productivity due to an aging demographic. For these reasons, many think Indonesia is on the rise.

Indonesia’s unique position in ASEAN as a massive market with eager young entrepreneurs is exactly what has made it a center of startups and innovation. For its vast population, Indonesians seek to create solutions for their environment. Additionally, neighboring countries such as Singapore often turn to Jakarta for skilled talent. In this section, we will look at what makes Jakarta’s startup scene powerful and promising, how its position on the world stage has led to innovations in the FinTech sector in particular, and what challenges still lie ahead.

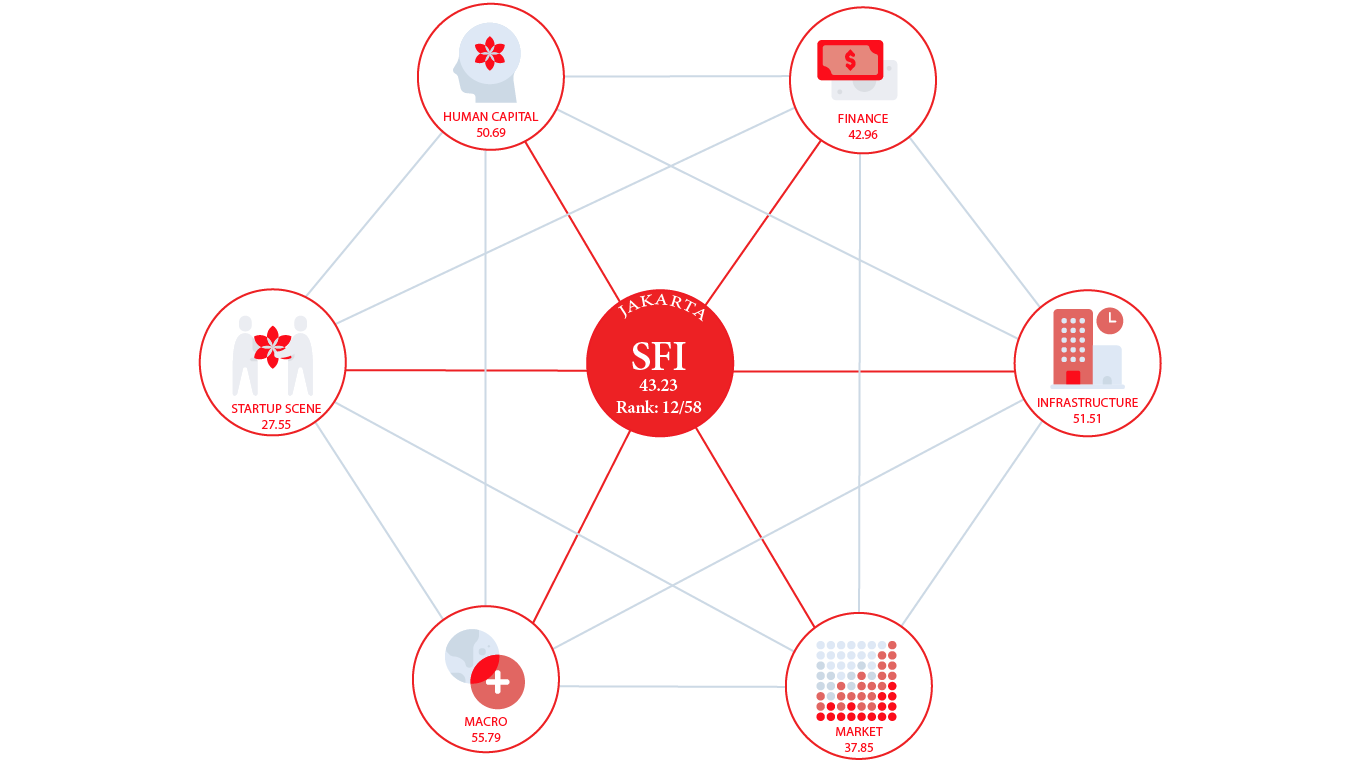

startup friendliness performance

In our SFI, from a list of 57 cities, Jakarta ranks in the 12th position after Chennai (India) and before Mexico City (Mexico) with a final SFI score of 43.23. Jakarta has major advantages relative to the average in domains like Market, Finance, Macro and Human Capital. In Human Capital, Jakarta stands out for the low salaries of both fresh graduates and software developers; in the Market domain, Jakarta benefits from the dynamics and size of Indonesia’s market; in the Macro domain Jakarta has made strides forward in Indonesia’s relatively fast and cheap business registration process and solid legal framework.

Improving human capital

Innovation requires talent and education. Jakarta has only one university (University of Indonesia) on the top 1000 globally according to the Times Higher Education “World University Rankings”, earning it a ranking of the 23rd position in the SFI.

I had the pleasure to talk with Aria Widyanto, the Director & Chief Risk and Sustainability Officer (CRSO) of Amartha, one of Indonesia’s largest peer-to-peer lending businesses.By living in the city of Jakarta and having so much knowledge on FinTech sector, his help was crucial in the enrichment of this piece.

Although Aria accurately describes Jakarta as “the center of the best talents in Indonesia”, internationally the city has been struggling to keep up in its curation of human capital. In 2017, 45,000 Indonesian students chose to study abroad rather than educate at home. The top destinations for Indonesian youth is Australia, followed by the United States of America. Despite this, Jakarta is still an anchor in the startup scene due to its sheer size and the potential talent therein, compounded by its economies lower salaries especially in comparison to other capitals in the region. The low salaries are a double-edged sword, though: while they are advantageous for young companies, higher salaries outside are a key factor in keeping or attracting higher skill talent and Jakarta cannot compete with other wealthier cities which offer better monetary conditions.

highlights

1. Low salaries are advantageous for startups

In Jakarta, average salary and minimum wage are among the lowest averaging $455 USD and 137 $USD respectively.

2. Simple and fast to start a business

In Indonesia, the process of business registration costs around $73 USD and takes 10 days, making it one of the fastest and cheapest processes among the countries in SFI.

3. Access to finance

In Jakarta, only 3.8% of firms consider access to finance a major constraint (score in our index of 82.66 out of 100 possible). When taking into consideration Indonesia as a whole, the value increases to 16.5%. Despite this, the average in Indonesia still trends better than the worldwide average of 25.9% of firms who view finance as a notable constraint. Access to loans is also significantly above average with a SME general score of 4.46 out of 7, thus ranking in the 12th position (out of 57 cities).

4. Indonesia has currently 5 unicorns and they are all based in Jakarta

With a valuation of $10 B US, Gojek was the first and largest company to reach unicorn status in 2016. It became a decacorn in 2019.

5. Startups in Indonesia are experiencing substantial growth.

So substantial, in fact, that the growth value for 2020 is based only on the first 8 months of the year, and the amount was still 66% higher than that for 2019. It represents an increase of activity in the startup scene. Additionally, due to Jakarta’s size, the number of startups is relatively high compared to the cities in SFI ranking at 12; in 2019, Jakarta had 821 startups, a number that had more than doubled – to 2492 – by the start of 2021.

6. The influence of external economies is considered low.

Economic trade openness (weight of imports and exports on total wealth generated) is lower than 40% (in Indonesia as a nation). Jakarta’s SFI ranking is 50th for influence of external economies.

Saturation … and relief

Quality of life is another barrier to attracting the right talent. Jakarta is a bustling city, but its infrastructure can be a major detractor even for natives, let alone international talent. The intense traffic, pollution and a rising cost of living are becoming concerning topics. With high pollution levels, our SFI Jakarta ranks only 35th in environmental quality and 41st in cost of living (around 980 USD monthly per person including a 1 bedroom apartment in the city center). Aria Widyanto lamented, “Jakarta is not really a livable city. It’s a difficult place to bootstrap your business, for instance. As it gets more international, it’s getting more difficult to live here.”

Still, challenges notwithstanding, the market size, market dynamics, the amount of talented people, the existence of solid technology infrastructure and the existence of already some big players in the ecosystem make Jakarta an attractive city. For that reason, Aria says “if you want to go big, go to Jakarta”.

He is not alone: Jakarta has grown into an oversaturated city filled with the hopes of millions of Indonesians. With the increase of industry and services during the 20th century, Jakarta attracted millions of rural Indonesians seeking better living conditions. The expansion of the city continued on from the center outward to the peripheries. Due to the accelerated pace of housing demand in the city, the quality of construction and urban planning suffered. Poorly constructed neighborhoods started to rise and merge into the city and shape the city itself. It is estimated that today the so-called “kampungs” are home to 25% of Jakarta’s population. These are characterized by high density populations (up to 4 people per square meter) despite the lack of tall housing units. For example, the Tambora slum houses 260,000 people within five square kilometres. Narrow streets, poor materials and small houses are blockers to efficient transportation systems, environmental quality and security.

The explosion has spilled over to traffic congestion. In 2019, it was estimated that, on average, each Jakarta driver spends yearly 150 hours in traffic congestion. From 2000 to 2010, the number of registered cars in the city grew from slightly over 1M to slightly over 2M. These factors give Jakarta a score of 43 in our index on road infrastructure quality. Besides increased time spent in transit, there is the stress and the pollution factors associated with high traffic congestion, giving its score for the Pollution a 30 in our index.

On top of widespread below-average infrastructure and a consistent positive population growth rate, Jakarta is literally sinking. It is estimated that some areas in the northern area of the city sink around 25 centimeters per year due to subsidence. As a result, Indonesia will move its capital from Jakarta to the province of East Kalimantan to relieve the city and create some political decentralization for the nation. With the relocation of such a crucial role, the population of Jakarta is expected to decrease in the short run and it should slow the growth rate in the long run.

a blue ocean of FinTech

Many of Jakarta’s early startup successes were not original business models. Often, they were adapted from other successful startups and adjusted for the Indonesian market. However, as is the case for many ecosystems in the region, Indonesia has its own unique set of challenges and its entrepreneurs are rising to meet the challenges. For Jakarta, this means the FinTech sector has been the site of renown innovation.

With a population of over 270 million, the majority of which is below the age of 35, technology is a key enabler for Indonesians. Around 185 million people have access to the internet (2020), and mobile subscriptions are as high as 415.7 million (more than one per person). Being composed of 17,508 islands, and the consequent lack of efficient transportation across the islands, creates remote areas where inhabitants have less access to infrastructure and services, not the least of which, banking.

Digital infrastructures overcome geography challenges quicker and cheaper than physical ones, and so advancements in FinTech were heralded in as the solution. In September 2019, there were 167 FinTech startups in Indonesia. By August 2020, that number had risen to 307, an increase of 83%. These startups tend to offer payment, lending, personal finance, crypto and blockchain, P2P (peer-to-peer) lending and investment, crowdfunding, insurtech, and PoS services.

Digital payments represent the bulk of the value of transactions, totalling over $30B USD. With traditional banking struggling to reach remote areas, less than 20% of the population had a bank account in 2011. Now, however, over 55% have access to digital banking. FinTech’s success has been helped by strict traditional banking regulations in lending; in 2018, the average interest rate for a SME business loan was 12.69%. The rate for non-performing loans (NPL) for SMEs in 2018 was only 3.35%, suggesting that banks have strict and higher standards for lending, constituting a barrier in accessing traditional bank loans. In this gap, peer-to-peer lending (P2P) has an opportunity to offer the speed, reach, accessibility, conditions where traditional banking fails in Indonesia. P2P also helps bridge the gap between FinTech and traditional banking; banks lend money to P2P in order to reach new customers that they couldn’t through the traditional methods, leading to a more robust finance sector in Indonesia overall.