Bengaluru: Creating local solutions for local problems

India’s startup scene as a whole started off by building on its imperial remnants. Large public sector companies in the manufacturing sector laid the groundwork for the emergence of an innovation cluster spanning different sectors such as electronics, machinery and aeronautics. This in turn led to the establishment of a number of public R&D institutions and universities. And so began a wave of in-migration of science and technology qualified labor force into the city.

The entry of Texas Instruments into Bengaluru in 1984 marked the beginning of another milestone in the growth of the city: it was dubbed as the “Silicon Valley of India”.

Overtime, the city grew a reputation for cheap IT labor. As it developed, it looked to address the “exclusive talent needs” of the Indian IT industry. An International Tech Park was created in Whitefield, Bengaluru, as the result of a joint venture between India and Singapore in 1994. This was followed by several other IT parks and, in the process, most major foreign software companies had set up development centers in India, overwhelmingly preferring Bengaluru.

Startups began to flourish as the talent hired by these large corporations began to develop into tech innovators themselves. Once lured by increased wages, skilled workers soon grew bored by the limitations of corporations and struck out on their own to create new companies. Today, the city is alive with a vibrant culture of tech enthusiasts and innovators. Corporations still play a large role in the ecosystem, often responsible for large innovation hubs, resulting in a diversity of companies and organizations across the business sector.

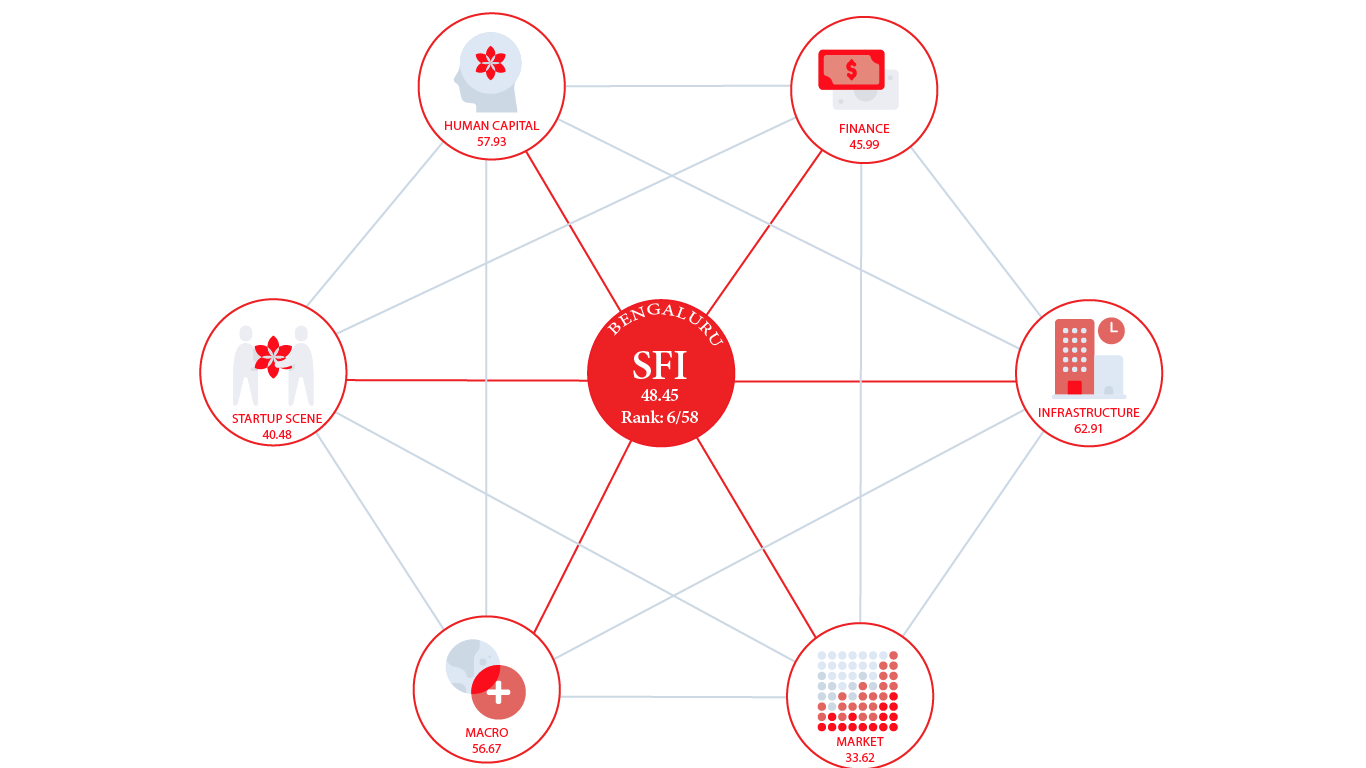

In this section we will look at how Bengaluru performs currently in the SFI, understanding how new waves of innovative solutions designed for India have erupted, and what role artificial intelligence and corporate innovations hubs have in the city today.

startup friendliness performance

Bengaluru has long been a regional powerhouse for startups. In our SFI, Bengaluru earns a score of 48 out of 100. It’s particular strengths show through in its Labour Market score, 77.02 out of 100, from conditions that do not restrict access to labour such as a low minimum wage and lack of legal constraints to hiring, both of which are advantageous to startups. Along the same lines, we see indicators that the entrepreneurial spirit is alive and well in Bengaluru. Furthermore, its ICT penetration is apt for a startup culture. There are droves of entrepreneurs hungry for a start in Bengaluru; however, they can lack proper access to funding and persistent inequality means there is a bias in terms of who can be part of the startup scene.

highlights

1. Entrepreneurial culture is alive and well in Bengaluru

In 1984, Texas Instruments expanded into the city, a time many consider the rise of the “Silicon Valley of India”. Our index shows that the city scores high for viewing entrepreneurship as a career path and the highest number of startups (100) with over 7400 listed; on the flip side, it ranks the worst for fear of failure (0).

2. Human capital is plentiful in Bengaluru

With a vast population, few regulations regarding hiring (workforce constraint: 99; labour regulation constraint: 95), and a low minimum wage ($54.50 USD monthly), Bengaluru is one of the easiest cities to hire in. More applicable to startups is the average salary of $777USD per month, which still pulls in at 80 in our index. Finding the right high quality talent, however, can depend on the sector of the startup.

3. Access to serious long term financing can be an issue

Our index shows that Bengaluru struggles in attracting a generous amount of funding. Its score for Seed & Pre-Seed funding pulls in at 17. “It would take 6-9 months for an investor to take a bet on you and the amount would not last you more than half a year,” says Ayushi. Startups funded by grants come in at a resounding 2.29 as well. Likewise, high equity funding of $5M and $1M come in at 40.39 and 23.21 respectively in the index.

4. Innovative startups are on the verge, but investors are struggling to make the pivot

Emerging from India is a growing trend of innovation from startups. While previously, many startups focused on replicating successful business models and applying them to the region, many startups are now focusing on creating new solutions, not only specific to their context, but that can scale up. Investors, however, still focus on less innovative, safer ideas.

Human capital aplenty

To help us understand how the startup scene in Bengaluru serves entrepreneurs, we turned to Ayushi Mishra, Co-Founder of Drona Maps, to discuss strengths, weaknesses, and areas for growth.

Ayushi’s perspective confirmed much of what our SFI revealed. “Because so many of the startups and service industry are tech-focused, it’s not as hard to find engineering talent to bring in. Our educational system has a strong focus on technical education,” she says. “What can be hard, especially for our company, which offers a niche innovative solution, is finding talent that has domain specific knowledge we require. So then, what we end up doing is spending at least 6 months training our employees before they can start contributing.” She is not alone. According to the Talent Shortage Survey 36% of Indian firms choose to train their own employees to meet their needs.

A lot of this is driven by the sheer size of the population. While there is a focus on IT and engineering colleges, the percentage of the population who can access them causes the indicator for University Students to lag to 7.53 in our global SFI.“Entrepreneurs like me, who have had the opportunity to have an elite education, are privileged in some ways with respect to access to networks. Much like the rest of the world there is definitely an element of educational bias at play.” Nonetheless, Bengaluru is known as an Indian education hub with 24 public universities, 12 deemed universities, 6 private universities, 207 engineering colleges, 61 medical institutions, 48 dental colleges, 280 management institutions , and more than 60 international schools.

Of course, this is not unique to India or Bengaluru, but can often be a challenge in countries with high human capital but low GDP per capita, where low salaries lend themselves to a low GDP per capita. India itself scores a 4.16 for its GDP per Capita indicator.

The good news is that in India, you can bootstrap for longer to prove your concept before you need access to large amounts of capital.

“Across the different cities in India you won’t see a huge difference in access to financing per-se, but the nature of startups is different. For instance, Mumbai has a large FinTech ecosystem as the financial capital of the country ,” Ayushi says. “You may find a difference in access to networks,” she adds. Indeed, Bengaluru sees a score of 65 for Loans Access and 99 for Funding Constraint. For total VCs/PEs, India receives a score of 12.14. Here, Ayushi says, what is also important to note is that there is still a bias in what VCs tend to invest in: “there is an investor bias towards B2B businesses in general, however, B2C startups that target scale have made it big such as Ola, OYO, Zomato, and Flipkart.”

But perhaps the most exciting aspect of the ecosystem is what Ayushi says is a growing willingness to innovate by Indian startups. “Three to four years ago, there started to be a shift,” she says. “Now, you’ll see more startups are creating new solutions which, yes, maybe are initially created for the Indian local context, but they are using the complexity of the Indian landscape as a good starting point for robust product development and are approaching global expansion faster.” In essence, she says, it’s a bit like how an individual artist may move from tracing pictures to innovating their own style. “We are in the phase where we are growing up.”

Ayushi spoke also of some growing pains associated with this change: “For my company in particular, since we work with emerging technology, the technical and financial details of large scale deployments have to be developed as we go. This translates to difficulty in finding an effective commercial onboarding model. However, there has been positive changes to ease this pain point, to the point where even government tenders have started including exemptions for certified startups, which is a step in the right direction to enable the adoption of the technology.”

Similarly, India’s national policies can present obstacles for startups like Ayushi’s. For a highly innovative field like drone mapping, it can be difficult to navigate the maze of legislation and regulatory offices to obtain all necessary approvals and clearances. Since 2018, pro-drone legislation emerged in India, allowing the pathway for more startups to operate in the industry. If these policies are not simplified, they could end up blocking innovative solutions from emerging.

Centers for startups

The city has come a long way since the nascence of its IT industry. When in the 1980s, aspiring tech giants, Infosys and Wipro, moved their offices to Bengaluru, the world began to see the city as a hub for IT. Large international and foreign companies began to look to Bengaluru as a source of cheap labor by hiring Indian developers and creating large contracts with IT centers. While the partnership was mutually advantageous for both parties, it has since evolved as the high tech environment soon gave way to genuine interest and new ideas. Over the years, a place unknown for supplying original ideas began to turn heads for new innovative ones.

Nowadays, Bengaluru and Karnataka in general houses more than 400 R&D centers. About 60% of biotechnology companies within India have a base in Bengaluru. The city is also home to several disruptive companies such as Flipkart, BigBasket, Mu Sigma, and Ola Cabs. The city is home to over 7,400 startups, making it the second in our index and ranks very high for how active its ecosystem is with on average 42 startup events per month.

There is also an established scene of accelerators, in particular large corporate incubators and innovation hubs such as Axilor, Kyron, and the Microsoft Accelerator, all of which focus on early-to-middle stage companies. The combined advantages of massive capital with young ideas have created a culture of innovation in the city that is quite unique and impressive.